The language of programming

I remember learning my first programming language. As a part of the required informatics class in the second grade, we had to study some dialect of BASIC. Slouched at our desks under dim fluorescent lights, we were throwing impatient glances at whirring IBM PCs placed along the walls of a stuffy classroom. The year was 1997, Russia. None of us had a computer at home. On a chalk-smeared blackboard, the teacher wrote:

SCREEN 15, 0

PSET (100, 100)

DRAW "R20 D20 L20 U20"

END

Joined by twenty pairs of bewildered eyes, my eight-year-old self stared at the presented “cryptogram” in incredulity. “Don’t feel intimidated” — declared the teacher in her soft-spoken, reassuring voice. She’d had us drawing flowcharts for several weeks leading to this lesson. We could already design detailed “algorithms” for peeling potatoes and assembling Legos. Still, the Latin characters glowering back at us from the chalkboard were foreign.

The teacher proceeded to decipher the program line by line. Avoiding English translation altogether, she assigned each lexeme a meaning and encouraged us to memorize them. After a while, we’d look at the program above and interpret it as if it was written in emoji.

🔲

➡️ 100

⬇️ 100

🖌 "➡️ 20 ⬇️ 20 ⬅️ 20 ⬆️ 20"

🏁

I still often think about this approach to teaching programming and how it bypasses the natural language link altogether. It’s amazing how a series of simple commands meant to be self-descriptive to an English speaker presents a serious coding challenge for everyone else. And coders we were. Twenty-something little compilers.

Abstract programming

Fast-forward ten years, I’m an undergrad studying algorithms and data structures. We’re writing C/C++, and every one of us knows English to some degree. Yet, all of our textbooks are in Russian, and again, the standard library function names are introduced without any hints at their English meanings. At the introductory lecture, the professor was presenting “Hello, World!” and other simple programs in C. He enunciated each function name slowly as he wrote it on the whiteboard. In his interpretation, getch() was pronounced “’ghat-che” and clrscr() — “ke-le-er-es-khe-ˈer”. Seems unbelievable now, but it would be a while before it clicked and I saw “get character” and “clear screen.” I’d then share my observations with fellow students, and they’d be as surprised as I was.

In hindsight, I can see how missing out on this natural language connection deprived us of some helpful context. And yet, this method of learning a programming language is compelling, because it’s so close to abstract math. It encouraged us to think of char *strstr(const char *haystack, const char *needle) as Ω(x,y). Even if a function had a confusing name, none of us would notice, because it wasn’t that much different from any other random lexeme we had to memorize. When you program this way, documentation is king and names are just links to underlying concepts.

Speaking of naming, in our own programs, we’d use mathematical notation mixed with Latinized Russian words. Due to the terse appearance and overall inscrutability of such code, professional programmers in Russia label it “govnokod”, which, translated, literally means “shitty code”. Yet, this is how programs built in academia often look like. And, to the angst of professionals, they work just as well as “clean” code does.

Some of my college friends who ended up in the software industry scorn the way programming is taught in Russian schools. Having had to learn to name their programming abstractions in proper English, they’re often full of angst towards the English-agnostic attitude to programming inculcated by the academia. This position interests me for two reasons:

- Learning a foreign language is hard. Contrary to popular belief, English is not easy to learn.

- Programming’s bond to naming is unusually strong even in comparison to other knowledge work fields.

Let’s review each point separately.

English is hard

In a blog post titled “English has been my pain for 15 years” the creator of Redis, Salvatore Sanfilippo talks about his decades-long struggle with expressing his thoughts in English. This is written by someone who built one of the cornerstones of the modern web stack:

…we were doing new TCP/IP attacks but we were not able to freaking write a post about it in English. It was 1998 and I already felt extremely limited by the fact I was not able to communicate, I was not able to read technical documentation written in English without putting too much efforts in the process of reading itself, so my brain was using like 50% of its energy to just read, and less was left to actually understand what I was reading.

For better or worse, we must agree that English has won the world’s common tongue competition. Fluent English reading is practically a requirement for doing any serious programming work. However, writing in a foreign language is even more challenging. On the one hand, a typical programming task doesn’t take a vocabulary you’d need to complete a passable short story. On the other, you’ll want pithiness and unambiguity in your names, and those don’t come naturally unless you’re proficient in the language.

I’d speculate that, on average, a relatively large API designed by a native English speaker will be more expressive than a similar API put together by a foreigner speaking intermediate English. This became particularly evident to me when I first came to Clojure. Rich Hickey is known for his deliberate use of vocabulary. In Clojure, simple is not easy, collections are not sequences, and functions with names like reify or transduce are commonplace.

Even armed with thesaurus or a reverse dictionary, a foreign speaker will struggle to match Rich’s semantic craftmanship. Still, reality proves that Google Translate and naming conventions get you far enough, and occasional blunders like isHided, visibles, unexisting are not critical to one’s star count on GitHub.

In general, a foreign speaker will do a fine job naming things in English, but struggle to describe a particular quality of an object, or distinctly label a certain kind of interaction. Think about young kids learning to speak. They’re much more likely to name a bunch of things around the house than to use words like “juxtapose” or “intersperse” to describe a complex action, or call something that randomly goes on and off “intermittent” (did I get it right?).

Names everywhere

The hackneyed old saying goes: “there are only two hard things in Computer Science: cache invalidation and naming things.” It’s not difficult to see why finding a good name can be challenging. Programs often deal with complex abstract data structures that don’t project well onto the “real world.”

Programmers can be incredibly creative when it comes to naming things. Chef, a configuration management framework, uses a whole set of cooking-related metaphors: cookbook, kitchen, knife, etc. Storm, a real-time computation system, operates on such entities as streams, spouts, and bolts. On a less practical side, Heroku entertains everyone with generated server hostnames like “flexile-sentry.heroku.com”. There’s an on-going debate about whether metaphors and “funny” names improve developer’s experience or just obscure the underlying concepts, but it falls outside the scope of this article. The point is, developers spend a lot of time naming all sorts of things. Sometimes, I’d argue, to the point of detriment to their productivity.

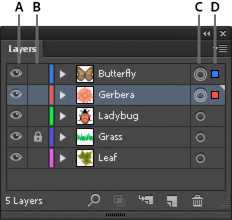

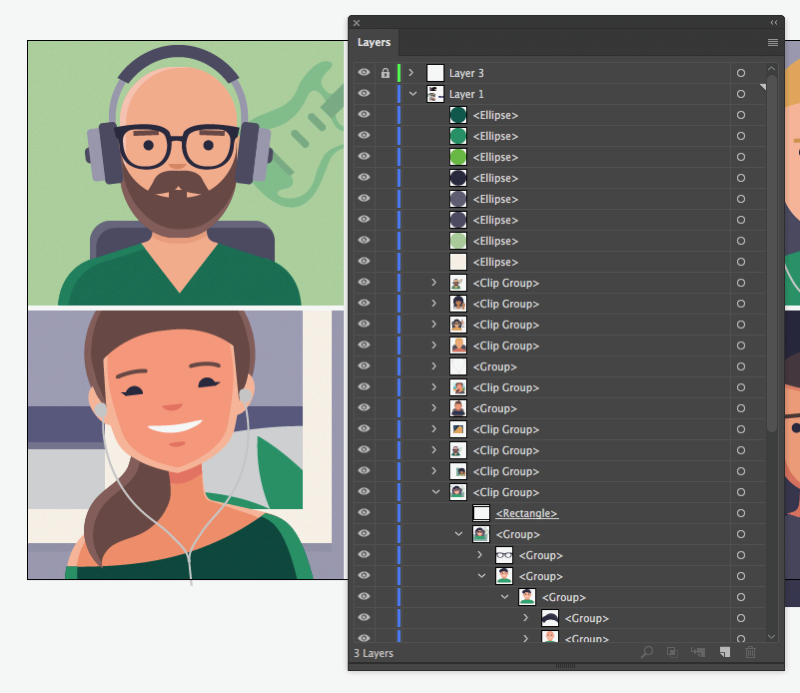

Occasionally, I get a good look at my wife’s computer screen when she’s working on a massive vector image in Illustrator or a web page mock-up in Sketch. Almost every advanced graphics editor has this little window listing all of the layers and figures in the current document. If you were to read the official manual to Illustrator, they sure recommend that you consciously name every element of the image.

And yet, when Julia is at work, this window looks nothing like the tutorials. She primarily relies on generated layer names and seems to navigate even rather complex illustrations without difficulty.

Illustrator doesn’t ask you to name your file upfront, neither it yells at you for having two layers with the same name. Get started with generated names, rename things as needed. Now compare this experience to bootstraping a fresh Ruby on Rails app. The required name argument is used for the application module, the session key, and inserted in the generated templates.

$ rails new experiment-2

...

$ grep -r -i experiment .

./app/views/layouts/application.html.erb: <title>Experiment2</title>

./config/application.rb:module Experiment2

./config/initializers/session_store.rb:Rails.application.config.session_store :cookie_store, key: '_experiment-2_session'

If you later decide to rename experiment-2 into SpaceElevator, you’re on your own. Even the most advanced Ruby IDE, RubyMine cannot pull off a trick as (seemingly) simple as renaming the project. And this is just the tip of the iceberg. If you think that “diamonds are forever,” you never explained a 10-year-old database schema to a new hire. Your worst names never stop to haunt you.

So, here we have it: naming is still hard. Even harder in a foreign language. Worse, changing names later is often difficult or practically impossible. How can we overcome these difficulties? Particularly, I’m interested in solving two problems:

- Enabling domain experts to use programming to advance their fields.

- Bridging the gap between the code produced by native speakers of different languages.

Fewer names = less naming

I’ve already mentioned Clojure above, picking on it for sophisticated, almost elitist approach to names. However, there’s a different side to it. Functional programming languages tend to require fewer unique names to get by. Several different concepts contribute to this:

- Function composition.

- Shorthand syntax for lambda functions.

- Naming conventions and “mathematical” notation.

Look at a Clojure snippet below. Here I introduce a function that returns only the terms (words) that occur more than a specified number of times in a given string.

(defn frequent-terms

"Split s into a sequence of lower-case terms, remove articles

and punctuation, return only terms that occur more than n times."

[s n]

(->> s

clojure.string/lower-case

(re-seq #"\w+")

(remove #{"a" "an" "the"})

frequencies

(keep #(when (> (val %) n) (key %)))))

(frequent-terms

"How much wood would a woodchuck chuck if a woodchuck could chuck wood.

As much wood as a woodchuck would if a woodchuck could chuck wood."

3)

; => ("woodchuck" "wood")

To implement this rather complex function, I only had to think of one name: the function name. I named the input string s, because this is the convention used by all string functions in Clojure, and, following another common convention, n denotes the only number accepted by the function. By composing several higher order functions, I avoid explicit iteration and its byproducts: indices and temporary variables. Even when I introduce a lambda function (#(when (> (val %) n) (key %)))), Clojure’s syntax doesn’t require me to name its argument, allowing its reference via the % character (multiple arguments can be accessed as %1, %2, etc.).

Not every function composition will have a good name. Again, mathematicians have avoided this problem by incorporating the Greek alphabet into their standard notation. While I wouldn’t recommend comprising your APIs out of Greek letters, a function-local helper can often be denoted as f or g without much harm, like in the example below.

(letfn [(f [x] (Math/pow (Math/sin x) 2))]

(f (transduce (map f) + [1 2 3 4 5])))

WTF is x?

While I do think that Clojure strikes an almost perfect balance between conciseness and expressiveness, I must admit I’ve been confused by these “mathematical” names on multiple occasions. Until you familiarized yourself with Clojure’s naming idioms, making sense of a function declaration can be a struggle. I’d still trade s, n, and f for string, min-occurrences, and squared-sine any day of the week, but for the sake of this experiment let’s explore other ways to improve readability without retreating to handcrafted names for everything.

The obvious answer is we could provide meta-information. Going back to the Illustrator example, the generated layer names still distinguish between different kinds of objects. For programming languages, this role can (to some degree) be played by type declarations and annotations. Let’s look at the following program written in Haskell:

repeat n x | n > 0 = x : repeat (n - 1) x

| otherwise = []

The repeat function accepts a number n and a value x and returns a list comprised of n copies of x. Haskell doesn’t usually require you to specify types, but you may choose to add type information to declare your assumptions to the compiler and other people reading your code. A type declaration for the repeat function could look like this:

; n x (return value)

repeat :: Int -> a -> [a]

This type signature informs the reader that n is an integer, x is a value of any type a, and the return value is a list of values of type a. While there is an infinite number of different implementations of repeat matching this type signature (e.g., returning n + k repetitions of a where k ∈ ℕ), the Haskell compiler can already catch a fair number of invalid implementations. For example, given a string x, the function won’t be able to produce a list of tuples or return a random value (or read the return value from a file). All of this is verified before the program is even launched. On the surface, this may appear like a win-win situation, but the reality is never black and white.

In theory, the stronger the language’s type system is, the more information is available statically, and thus the more powerful refactoring and code inspection tools can be made for that language. Sure, Java, Scala, and C# instrumentation built into IDEA and Visual Studio are more reliable than their Ruby’s counterparts. At the same time, there is also a paradox when Haskell developers tend to abstain from using any tooling except for the compiler, while the lispers reap many of the same benefits (and some others) by having their editors connected to an interactive environment (REPL).

While an improvement over “just names”, a type system alone doesn’t magically make the code in “mathematical” notation self-documenting. For example, compare the following declarations of the strstr C function that searches for the occurrences of one string within another:

# 1.

char * strstr(const char *a, const char *b);

# 2.

char * strstr(const char *haystack, const char *needle)

Number #2 makes the order of the arguments immediately clear to any English speaker familiar with the “needle in a haystack” idiom. At the same time, this again brings us to the problem where #1 and #2 are equivalently baffling to somebody who is not fluent in English.

The limits of plain text

Where does this leave us? Functional programming and advanced type systems sure reduce the number of names we have to memorize and invent to produce useful programs. But there are always going to be functions like strstr that are inscrutable without either understanding the context supplied through the natural language semantics or perusing documentation. Now, an English speaker might wonder why those poor foreigners won’t just build programming languages based on their own vocabulary and alphabets? They do exist, but such attempts are destined to isolation in a field that has been built on the integration of ideas.

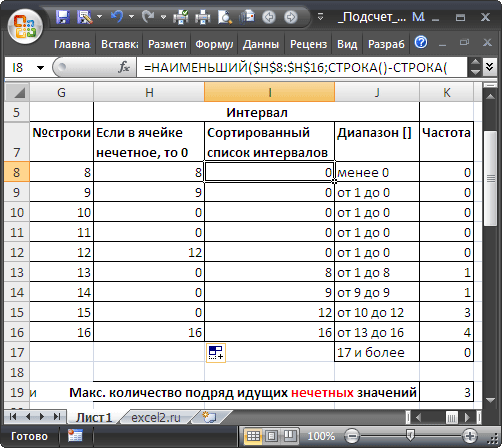

Instead, let me give you another example. On a screenshot below, a spreadsheet is being edited in a Russian localization of Microsoft Excel. The curious thing about the Russian Excel is that its built-in function library has also been internationalized, so you type the function names using Cyrillic.

I won’t lie, this looks outrageous even to me. But not to my Dad, who is a civil engineer and doesn’t speak a word of English. He is dangerously fluent in Excel’s formulas, which he uses extensively in those hundred-sheet documents bristling with filters, conditionals, and pivot tables. Then the roads and bridges are getting built based on those calculations. He doesn’t know what IF means, but he uses ЕСЛИ all the time. What’s amazing is that if he emailed you one of his spreadsheets and you happened to open it in your “real deal” MS Excel, every formula would appear in English, but work just as he intended.

Now imagine receiving a thousand line long piece of “govnokod” I demonstrated above. You’ll probably get it to compile, but good luck making sense of the API comprised of Latinized Russian words and Greek alphabet. I don’t know how we get to the level of cosmopolitanism exhibited by Excel on a scale of a “real” programming language. What’s apparent is that this is one of the cases where limitations of plain text as a primary medium for writing and distributing programs come to the fore. Excel can do this because they control both the format and the development environment.

Some programmers become extremely defensive when it comes to discussing alternatives to plain text. The “bible” of many contemporary programmers, “The Pragmatic Programmer,” which I read and reviewed on this blog, dedicates an entire section to describing the plain text as a shuriken of pragmatic programmers. Still, with increasing proliferation of advanced IDEs (which already obscure some implementation details) and wider adoption of non-textual programming environments (e.g., MIT Scratch or Unreal Blueprints), it seems more and more plausible that there’s something on the horizon that will combine all these ideas and yield a practical programming tool for everyone.

Recap

This post was born out of my frustration with names as identifiers, and in particular, the rigidness of once chosen names in a field as malleable as software development. I occasionally find myself stuck choosing a descriptive moniker for a new project, function or variable. In part, this is because naming is hard, in part — because English isn’t my native language. But there remains an area where the difficulty in naming is induced by our current programming tools and techniques.

Functional programming reduces the number of unique names in a program. Type declarations provide an extra layer of meaning and allow the use of mathematical notation without a hit to readability. Static type verification and stricter compilers make it easier to build more advanced refactoring tools, which allow bad names to be changed later. In this post I tried to demonstrate how these trends and other ideas can help bridge the gap between different cultures through universal computing.

Perhaps, the greatest improvements in this area lie in going beyond traditional programming tools (e.g., text editors and CLI) towards purely visual, interactive environments. As absurd as it sounds, in order for programming to become the “tool for thought” it’s been promulgated as, it must learn the lessons of Excel and Illustrator, it must remain open to new ideas and not outright discard them as “impractical”. In other words, our computers have to learn the universal language: empathy.