A look at Uncharted 4

When The Last of Us came out in 2013, I bought a PlayStation 3 just so that I can play it. I hadn’t been keeping up with latest trends in action games, so Naughty Dog’s creation appeared refreshingly novel to me. The game had impeccable art direction; brutal, realistically hectic combat, and a disarming story to piece it all together. Add the mesmerizing soundtrack by Gustavo Santaolalla (“Amores Perros,” “Biutiful,” etc.), and the long streak of received awards seems inevitable.

Though I enjoyed the action sequences, my most cherished moments of The Last of Us were those long eventless hikes through desolated landscapes of the post-epidemic US. The developers at Naughty Dog would make the most of every such break to familiarize the player with the characters and do some environmental story-telling.

In a video review of The Last of Us, Chris Franklin (Errant Signal) accentuated the dichotomy between the story and the gameplay. While I can understand his critique, the two parts still formed a cohesive whole in my mind. The always-looming danger that contaminated even the most peaceful moments was just another invention that made this world feel real. The characters acted like people traumatized by their choices, but who learned to persevere. Putting the genre restrictions aside, The Last of Us remains one of my favorite games, while the moments like Ellie casually reading puns from “No Pun Intended” (“3.14% of sailors are Pi Rates”) stay with you for life.

Every once in a while, when I’d talk to another admirer of The Last of Us, they’d endorse the Uncharted series by the same developer. At first, I had zero interest in what sounded like an Indiana Jones adaptation, but the years of mentions by friends and the press did their job. Just about a month ago, upon noticing Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End (the latest incarnation of the series for PlayStation 4) go on sale — I grabbed it without a second thought.

Uncharted 4 makes a bold first impression. An unplanned escape from a jail in Panama blurs into a childhood memory of Nate Drake sneaking out of a Catholic boarding school in the middle of the night. These two action-packed sequences are set apart by a relaxed ascent onto a tower with the Henry Avery’s prison cell (and an awkward puzzle) waiting atop. Despite the entire sequence being presented in a vivid art style reminiscent of modern Bond movies, the kinship between Uncharted and The Last of Us is immediately evident.

Following the intro, the game jumps fifteen years into the future. Nathan, now a retired treasure hunter, lives a self-imposed ordinary life with his wife Elena: a columnist for a travel magazine. Despite the cliché setting, the scene unveils naturally and duly serves the purpose of introducing the player to the couple’s relationship. They share dinner, and then Nate challenges his wife to beat her score in the original Crash Bandicoot (you get to play). Later, in a moment of awkward silence, Elena asks Nathan: “Are you happy?”

By this point, the protagonist appears as a man encumbered by guilt who embraced a mundane life to protect everyone from the dangers of him being his “true self.” He is a “tired hero” stereotype, but a convincing one. It’s evident that his normal routine is on the verge of collapsing, and Naughty Dog doesn’t linger on it for too long. In no time, the game makes a rapid turn, and the main story centered around Henry Avery’s treasure starts to unwrap. With this, the gameplay takes an unexpected turn.

What immediately stroke me in the early game is the amount of undue violence. Other characters often call Nathan a thief, but in reality, he is more of a psycho killer. When Joel from The Last of Us had to “kill or be killed” (and that life turned him into a morose skeptic), Nathan slaughters hundreds of “evil mercenaries” without losing his love for adventure and a charming smile. There remains a significant chunk of stealth element, but the game encourages a more aggressive play style that combines quiet takedowns with open combat. To make sure you don’t spend too much time hiding in tall grass, the level designers will occasionally unleash armies of various enemies onto you, sending Nate and his mates scurry from cover to cover to survive.

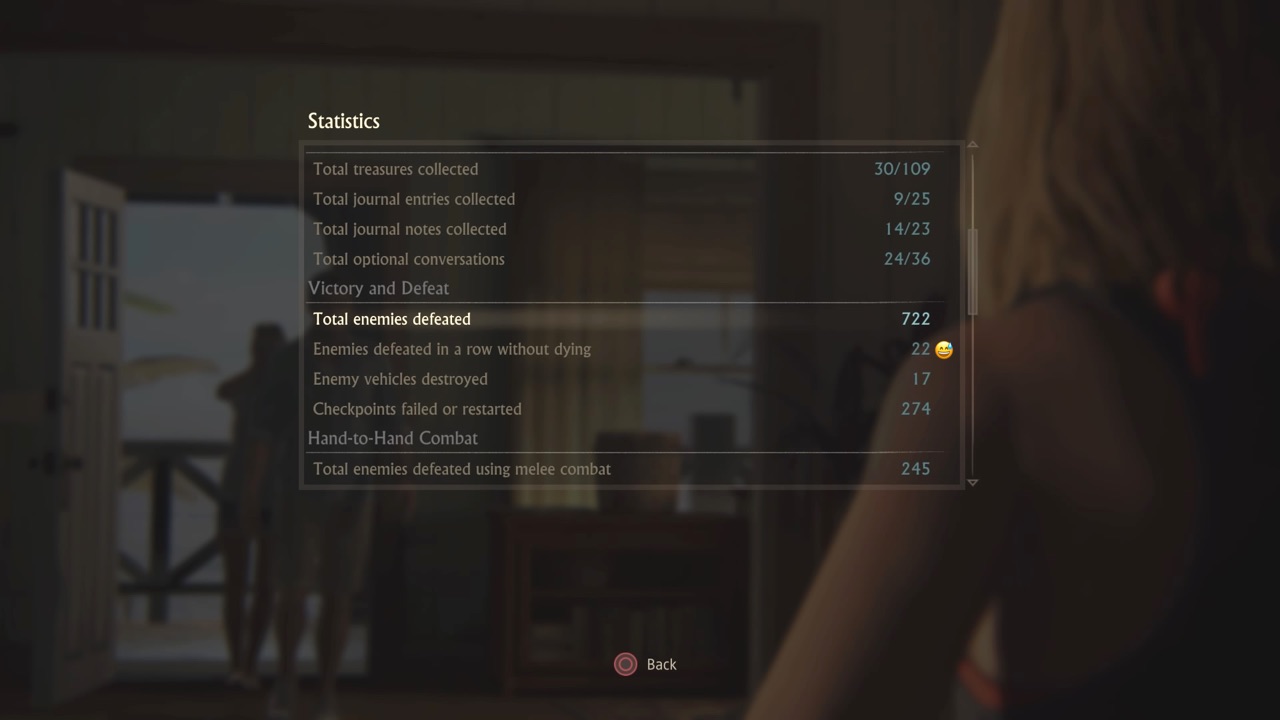

When Elena re-enters the story later in the game, for a moment there’s hope that she’ll serve as a moral compass for the male protagonists. It happens (somewhat), but the effects of her influence are noticeable only in cutscenes. Throughout the gameplay, she acts as yet another murdering uber-ninja-commando. At this point, the situation becomes almost comical. The Drakes will cold-handily massacre three dozen men and then suddenly feel like having another “you don’t trust me” family squabble. The storyline ends up being fully disconnected from the gameplay. During my playthrough, I had to kill 722 “enemies.” One would think that such experience leaves a trace in a character’s soul (spoiler alert: no).

In between the cutscenes, you climb buildings and mountains, take cover at first sight of enemies, stay under the radar for as long as possible, then kill the rest. This core remains unchanged throughout the game. Occasionally, you can pass a location without killing anyone, but more often than not it’s just too hard to understand where you’re heading without clearing the area first. And regardless, there’s just no challenge in Uncharted 4 beyond killing hordes of mercenaries that are occasionally dispatched your way, so why not indulge in it. The climbing is practically automatic, the puzzles are perfunctory (Nathan mostly solves them himself), and the driving physics are so unrealistic that you are grateful that it’s not a large part of the game. What ultimately keeps one going (kept me going, at least) is the surroundings.

Naughty Dog has made another technological breakthrough with Uncharted 4. It is undoubtedly among the best-looking game on PlayStation 4. I’d routinely stop to take a screenshot of some particularly breathtaking view, each time thinking it can’t get any more beautiful, and yet being caught off guard again and again. I wish I could say that Uncharted 4 is a perfect site-seeing game with some questionable morale, tedious action sequences, and trivial puzzles. But no, it can’t even get this one thing right. On the one hand, it undoubtedly wants you to marvel at its visual art and explore the terrain: there’s a built-in photo mode, an entire game mechanic of collecting hidden treasures, and also Nate’s sketches of objects of interest. On the other, try spending more than a few seconds wandering around, an annoying sound will remind you of your current goals, or Nate will start telling you what to do himself (“I wonder if I can move that bookshelf over there”).

Despite the technical perfection, Uncharted 4 is also the first game where I found that improved graphics aren’t just a source of awe, but also of uncanniness. Take the climbing mechanic: you’ll spend a fair share of the total playtime clambering various steep objects. “Climbable” surfaces will have very distinct ledges visible from a distance. These cues of game design stand out in the realistic art style, which is unarguably intended but still feels almost like seeing Mario platforms beneath the guise of photorealistic landscapes.

One may argue that these artifacts are unavoidable in a video game, and I’d agree, but it’s not only their presence but also their absence that throws you off the track. For example, not far into the game, Nathan and his brother are making their way through a narrow tunnel of an unstable cave. A collapsed beam stands on their way, but there’s clearly enough room to get around it. Yet, they decide to move the beam instead. I’d let it pass if it happened just once, but the game is full of this kind of unpredictable behavior. Sometimes the characters will help each other reach a particular ledge, and other times ignore a possibility of the same maneuver in a similar situation. Of course, there will be a crate somewhere in an adjacent room that you can employ to reach the desired height, but these restrictions imposed by the game designers seem almost humiliating. “I know how you want me to get there, do I have to?” If this is not the territory of the uncanny valley, what is?

Note: Aforementioned Chris Franklin has also raised a question of photorealism being a vain pursuit that might be hurting video games more than it helps them. I highly recommend it.

Uncharted 4 is afraid that you’ll get bored. This fear results in the kind of game design that values quantity over quality. Instead of introducing a new mechanic and letting the player master it, the game keeps throwing more stuff at you at a surprising rate. Hey, here’s a car, it has a winch that you’ll use three or four times (don’t worry we’ll highlight a tree or beam you’ll need to hook it up to from within a mile). Oh, and here’s dynamite that you can destroy doors with (used it twice?). Here’s a boat… ah, never mind. The apotheosis of this trend is the final “boss battle” that fully relies on you mastering a whole new mechanic and a set of controls on the spot. Thus, instead of testing your acquired skills, it ends up being a frustrating sequence of dying and having to replay this minigame you never asked for.

Uncharted 4 is full of conflicts: it’s a game about exploration that holds your hand throughout the adventure. It’s a story that is at odds with the gameplay. Finally, it’s a toothless shooter lacking the satisfaction of being in power and a stealth action that’s too tedious to play stealthily. This game wants to be so many things at once and fails at almost every one of them. I’m bewildered by the high praise from the critics and amazed that the game is marketed to a younger audience than The Last of Us. Perhaps, what annoys me the most is how Uncharted 4 manages to corrupt my appreciation for The Last of Us by mangling its best strengths.