Bloodborne

It is all thanks to yourself. — Anonymous Hunter

Despite buying Bloodborne on the release weekend, it took me almost 6 months to trudge through the game to the easiest ending. I’d give up for weeks, only to return again, as if I was a hunter stuck in the night of the hunt.

One thing I realized early on — though struggled with until much later — Bloodborne refuses to play by the rules of other contemporary video game titles. While it is entertaining and fun at times, its core is a cultural experience that will demand the entirety of your focus. Think a Gaspar Noé’s movie or a Thomas Ligotti’s book — dark, solitary and unwelcoming. Bloodborne is hardly a good choice to wind off after a bad day at work.

As you can read in the countless reviews around the web, Bloodborne is akin to the Souls series by the same developer. While I understand the appeal of the Souls games to hardcore gamers, I see Bloodborne as something bigger than the old mechanics with a fresh face. Even though neither the visual aesthetics nor the overall tone are particularly sophisticated, there is a sensible presence of a hidden dimension that ties it all together.

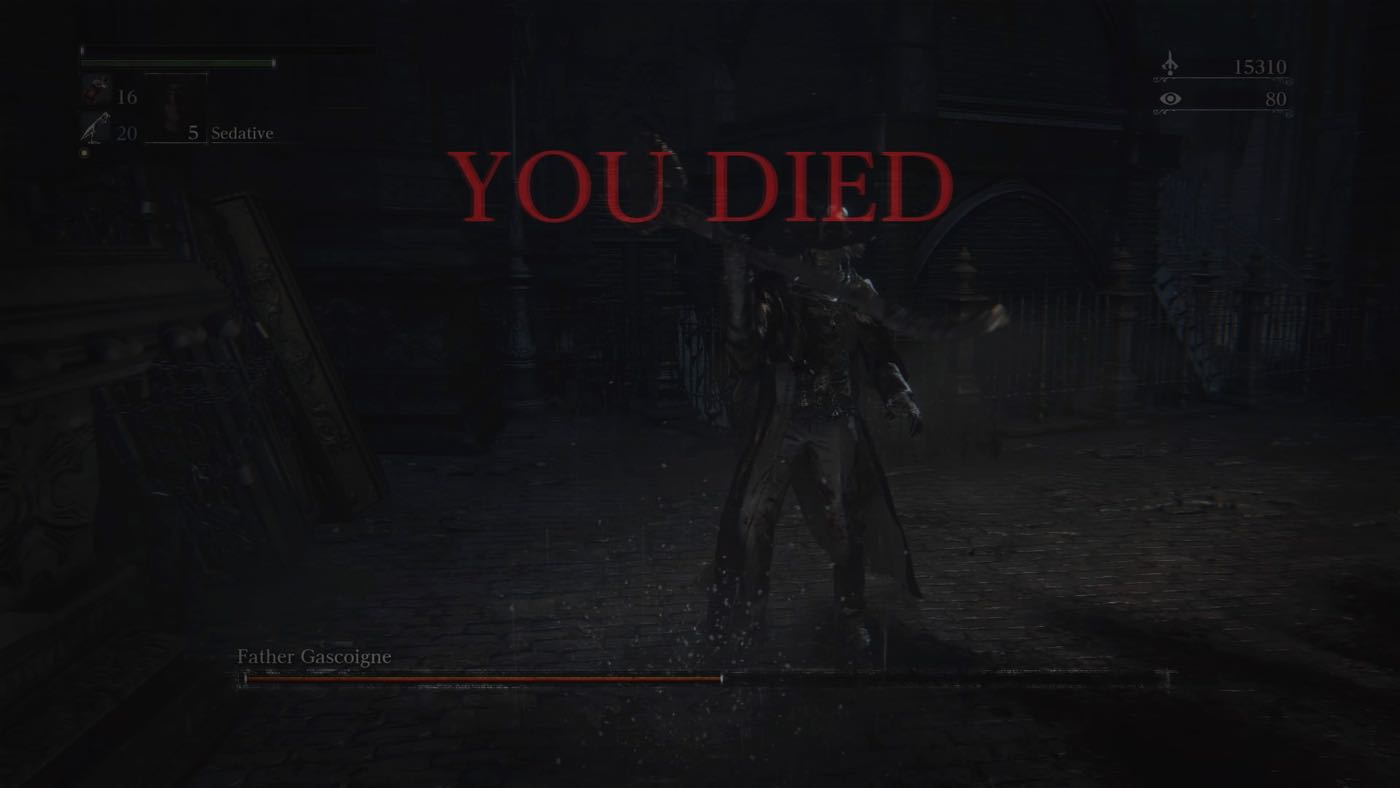

One of the keys to enjoying Bloodborne is ceasing to treat progress in terms of “getting somewhere,” and learning to enjoy the game’s cyclic design. All these frantic “survival loops” running between limited safe places turn out to be the ultimate discovery of game director Hidetaka Miyazaki. There is no way to save the game, and neither you can put this nightmare on pause. The price of a mistake is high: you die and lose all acquired blood souls (the in-game currency used to purchase equipment and character upgrades), waking up by the last visited “safety lamp”. This fear keeps you alert and makes you interact with the world in ways uncommon for a video game. You walk instead of running, listen for every faint rustle, indistinct whisper, or labored breathing around the corner. Soon, you’ll learn signature sounds of every beast. And yet, this won’t be enough to make you invincible.

The action here has a subtle timing. Like a dance, it requires a great deal of muscular coordination. As I’m a terrible dancer, I’d rush my moves, lose orientation, and die, again and again, defeated by this unforgiving rhythm. The same rhythm that every other creature seems to understand intuitively. You are the intruder in a world owned by beasts, and learning to survive means becoming one yourself.

The daunting feeling of desolation and solitude grows even stronger when exploring the randomly generated chalice dungeons. As the level design loses human touch, you really come to understand the cruel and unforgiving nature of Bloodborne. I can’t tell how much of what I encountered down in the old labyrinth was directed, and what could be accounted to the trickery of Great Random, but nowhere else in the game I saw rooms packed of beasts so full, you just can’t beat them in an open fight.

This contrast in events density between chalice dungeons and the main track made me realize what Bloodborne occasionally reminds me of. A game mod put together by a loving fan. It’s not to say that Bloodborne is in any way unprofessional or lacking in production quality. It’s that you can almost hear Miyazaki laughing when a wolf-like beast sneaks behind your back and tears you apart. The intentionality of every single encounter gives the director away. This sort of connection to the game designer is rare, and is something to be cherished.